Breaking the cycle of forced intergenerational sex trade with youth as agents of change

In the mid-1980s, Paramita Banerjee found her changemaking spark with a vision to challenge paradigms that deny agency to the youth wanting to change their environments, specifically to the youth and children who grow up in red-light districts.

Paramita started with volunteering at organisations devoted to protecting the welfare of sex workers in the red light districts of Kolkata, a city that is home to 50,000 sex workers, the largest among all Asian cities. Paramita believed the forced brothel-based sex trade was the epitome of patriarchal society-induced exploitation and discrimination.

Young girls born in brothels would be taken away from the red-light districts to be put in shelter homes and brought back to the red-light districts when they turned 16*. Shortly after their return, they would be married off by their mothers or would elope themselves with their partners in hopes of a better life. However, within a year or two, these young girls would be sold off into the sex trade somewhere else in the country by their supposed husbands or partners or be forced to return and join the trade because of severe domestic violence faced mostly because they come from red-light districts, setting off a vicious loop of the intergenerational sex trade.The notion that women have a choice does not stand in these areas, due to entrenched systemic inequities like lack of access to education, training and other means of livelihood, perpetuated by the system over generations on.

Over the years of her work in red light districts, Paramita noticed a stark abberration that while numerous interventions were being undertaken by civil societies, NGOs, government agencies, these interventions had very little or no engagement with young boys living in these areas, and alarmingly, very little engagement with the families of sex workers and sex workers themselves. Children born in these red-light districts, would be subjected to skewed gender dynamics, stigma, and discrimination, resulting in school dropouts and internalised shame. And young boys would grow up with no role models and end up peddling drugs or succumbing to other forms of juvenile delinquency.

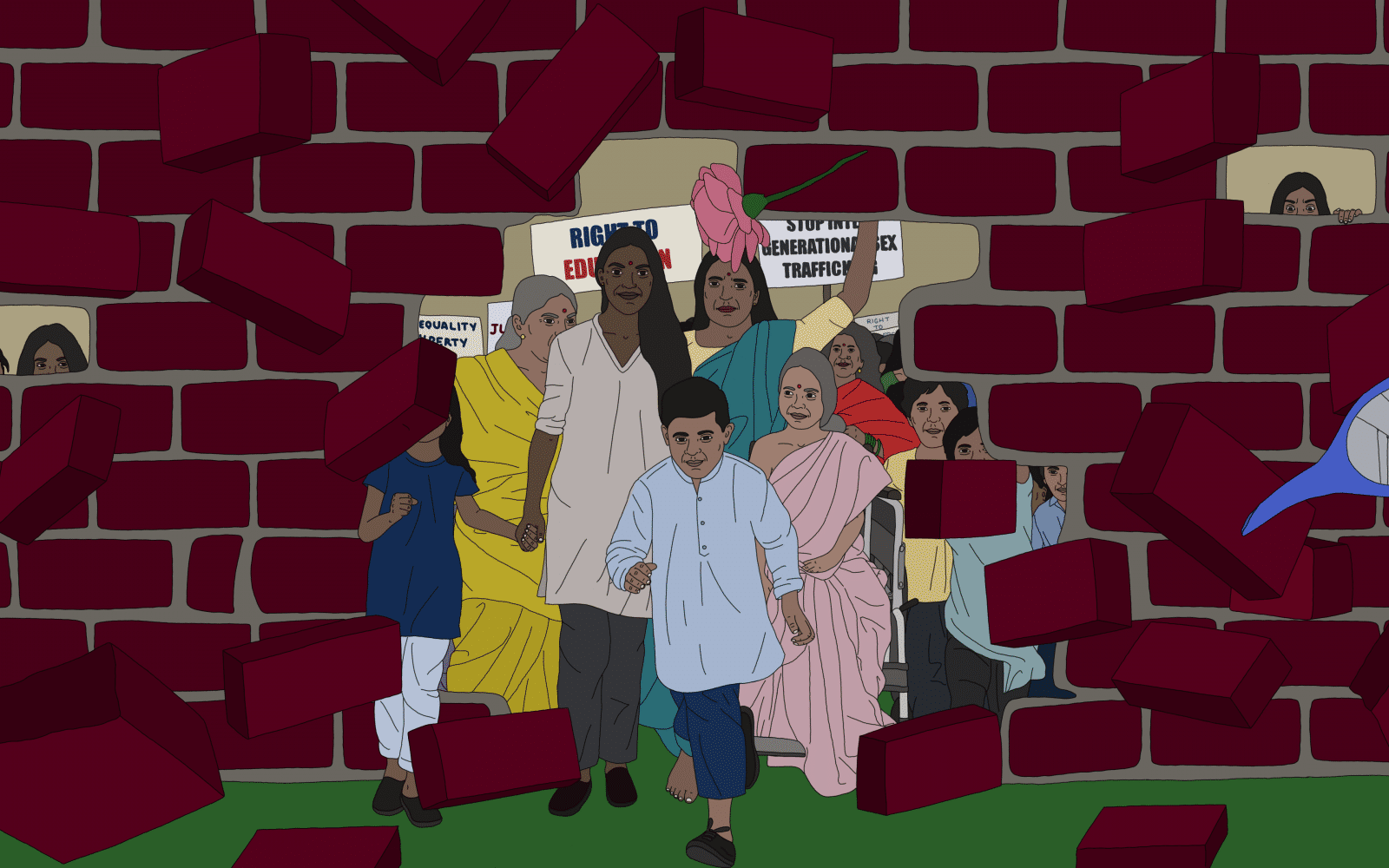

A question from a 15-year-old, at a workshop on sexual and reproductive health that Paramita was conducting, changed her whole perspective: Why can’t boys say no to underage marriage? Why are boys left out of sexual and reproductive health and rights workshops? This led Paramita to develop co-ed workshops, sensitising young boys and girls alike. DIKSHA was borne out of 16 such adolescents in one of Paramita’s workshops, from the Kalighat red-light district that wanted to establish a programme specifically for adolescents, and that is why Paramita calls herself the incidental 17th co-founder.

Through the sustained work of the youth in DIKSHA, ward 83 in Kalighat, Kolkata is now termed as a child-safe ward, with no instances of minors engaged in sex work or dependent on the sex trade economy